Karma, Saṃsāra, and Mokṣa

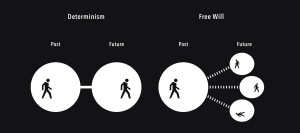

Karma is another central concept in the Indian philosophical tradition that finds some of its first philosophical articulations in the Upaniṣads. Literally meaning ‘action’, karma emerges out of a ritual context where it refers to any ritual action, which, if performed correctly, yields beneficial results, but if performed incorrectly, brings about negative consequences. The Upaniṣads do not offer any explicit theory of karma but do contain a number of teachings that seem to extend the notion of karma beyond the ritual context to more general understandings of moral retribution and of causality. Yājñavalkya, for example, when asked by Ārtabhāga about what happens to a person after death, responds that a person becomes good by good action and bad by bad action (BU 3.2.13). Here and elsewhere, one of Yājñavalkya’s fundamental assumptions is that present actions have consequences in the future and that our present circumstances have been shaped by our past actions. While this law-like character of karma suggests that the consequences of one’s actions shape one’s future, Yājñavalkya does not give any indication that the future is completely determined. Rather, he seems to suggest that one can create good consequences in the future by performing good actions in the present. In other words, Yājñavalkya presents karma more as a theory to promote good actions, than as a fatalistic doctrine in which the future is fixed.

While Yājñavalkya assumes that karma takes place across lifetimes, he does not attempt to explain the mechanisms of rebirth. In the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, however, King Pravāhaṇa Jaivali is more specific about how karma and rebirth operate, describing the link between them in terms of a naturalistic philosophy (CU 5.4-10). In a dialogue that also appears in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (BU 6.2.9-16), but without the explicit connection to karma, Pravāhaṇa discloses the teaching of the five fires (pañcāgnividyā) to Uddālaka Āruṇi. Pravāhaṇa’s instruction describes human life as part of a cycle of regeneration, whereby the essence of life takes on different forms as it passes through different levels of existence: when humans die, they are cremated and travel in the form of smoke to the other world (the first fire), where they become soma; as soma, they enter a rain cloud (the second fire) and become rain; as rain, they return to earth (the third fire), where they become food; as food, they enter man (the fourth fire), where they become semen; as semen, they enter a woman (the fifth fire) and become an embryo. According to Pravāhaṇa, those who know the teaching of the five fires follow the path of the gods and enter the world of Brahman, but those who do not know this teaching, will follow the path of the ancestors and continue to be reborn.

Pravāhaṇa states that knowledge of the teaching of the five fires will affect the conditions of one’s future births. He explains that people who are pleasant will enter a ‘pleasant womb’ such as the womb of a brahmin, a kṣatriya, or a vaiśya. But that people of foul behavior can expect to enter the womb of a dog, a pig, or an outcaste (CU 5.10.7). In this teaching, Pravāhaṇa demonstrates the link between karma and rebirth by specifying different types of animals (dogs, pigs) and different types of matter (smoke, rain, food, semen) through which karma operates. By implication, karma not only applies to the causes and effects of human actions but also includes non-human animals and other forms of organic and inorganic matter. Moreover, karma is not directed by a divine being but rather is described as an independent, natural process. As such, karma is presented as an impersonal moral force that operates throughout the totality of existence, balancing out the consequences of good and bad action. Here, we see that Uddālaka Āruṇi’s teaching implies that everyone’s actions have moral consequences and that all the actions of humans and non-humans are interconnected.

Such discussions linking actions in one lifetime to consequences in a future one would become widely accepted in subsequent philosophical discourse—not only among Hindus, but also by Buddhists and Jains, and, to a certain extent, by the Ājīvikas. In subsequent developments across these traditions, karma would often be conceptualized in terms of intention and much of what we might describe as ethics was to be focused on ways to cultivate a state of mind that would generate positive rather than negative intentions.

Despite the development of ideas about karma, the earliest Upaniṣads generally do not contain the assumption that life is suffering (duḥkha), or illusion (māyā), or ignorance (avidyā)—views that would later dominate discussions of karma and rebirth. Nonetheless, we do see the introduction of the term “saṃsāra” in the comparatively late Kaṭha (3.7) and Śvetāśvatara (6.16) Upaniṣads. Literally meaning, ‘that which turns around forever’, saṃsāra refers to the cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth. All living creatures, including the gods, are considered to be a part of saṃsāra. Accordingly, death is not considered to be final, and rebirth is an essential aspect of existence.

Closely related to saṃsāra is mokṣa, the concept that one can escape or be released from the endless cycle of repeated births. Similar to saṃsāra, the Upaniṣads do not contain an explicit theory about mokṣa, with the term “mokṣa” only assuming its connotations of liberation in the later texts (that is, SU 6.16). The Hindu darśanas would subsequently consider mokṣa to be fundamental teaching of all the Upaniṣads, but the texts themselves, particularly the early ones, focus much more attention on securing wealth, status, and power in this lifetime than on describing existence as an endless cycle. They also tend to present life as desirable, and not as a condition from which people need a release or escape. One of the most common soteriological goals is immortality, amṛta, which literally means ‘not dying’. The Upaniṣads describe immortality in different ways, including having a long life span, surviving death in the heavenly world, becoming one with the essential being of the universe, and being preserved in the social memory.

Ethics and the Upaniṣads

Philosophy in the Upaniṣads does not merely consist of abstract claims about the nature of reality but is also presented as a way of living one’s life. In Yājñavalkya’s teaching to Janaka, for example, knowledge of ātman is associated with a change in one’s disposition and behavior. As we have seen, karma is characterized as a natural moral process, with knowledge of the self as a way out of that process. In this respect, a fundamental assumption throughout many teachings of the self is that it is untouched by karma. Yājñavalkya teaches Janaka that knowledge of the self is beyond virtuous (kalyāṇa) and evil (pāpa)—that, through knowledge of the self one reaches the world of brahman, where the good or bad actions of one’s life do not follow (BU 4.4.22).

Yājñavalkya explains that in the world of brahmana thief is not a thief, a murderer is not a murderer, an outcaste not an outcaste, a mixed-caste person (paulkasa) is not a mixed-caste person, a renunciate (śramaṇa) is not a renunciate, and an ascetic not an ascetic, that neither the good (puṇya) nor the evil (pāpa) follow him (BU 4.3.22; see also TU 2.9.1). In using these examples Yājñavalkya illustrates the degree to which knowledge of the self is beyond everyday notions of moral behavior. In other words, he seems to be saying that even if one has committed evil deeds, one can still be liberated from karma by means of knowing the self. Yet Yājñavalkya is not suggesting that one can continue to perform ‘evil’ deeds without suffering karmic retribution. Rather, as he asserts later in his discussion with Janaka: when one is knowledgeable, one necessarily acts morally. Yājñavalkya explains that a man who has proper knowledge becomes calm (śānta), restrained (dānta), withdrawn (uparata), patient (titikṣu), and composed (samāhita) (BU 4.4.23). Here Yājñavalkya characterizes knowledge of the self as a change in one’s disposition. In other words, one who is a knower of the self becomes a person of good character and—by definition—would not perform an evil action.

While Yājñavalkya talks about becoming calm, restrained, withdrawn, patient, and composed, these dispositions are not presented as virtues to cultivate for the sake of knowledge, but rather as consequences of knowing ātman. Subsequent texts would devote considerable attention to how one should cultivate oneself in order to achieve the highest knowledge. For example, both the eight-fold path of the Buddhist Nikāyas and the eight limbs in the Yoga Sūtra suggest that one needs to live a moral life in order to achieve true knowledge. In Yājñavalkya’s teaching about ātman, however, there is more attention paid to the objective of knowing the self than the ethical means of controlling the self.

Despite the lack of details about the path to knowledge, Yājñavalkya nevertheless connects knowledge of ātman with particular practices, explaining to Janaka that brahmins seek to know ātman by means of Vedic recitation (vedānuvacana), sacrifice (yajña), gift-giving (dāna), austerity (tapas), and fasting (BU 4.4.22). Yājñavalkya elaborates, claiming that by knowing the self, one becomes a sage (muni), undertaking an ascetic and peripatetic lifestyle (BU 4.4.22). Here, Yājñavalkya implies that those who come to know ātman will become renunciates—that knowledge of the self not only brings about certain dispositions or a certain character but also provokes a particular lifestyle. Similarly, in the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad, Aṅgiras teaches Śaunaka that the self can be mastered by means of asceticism and celibacy, among other practices (MU 3.1.5).

With the connection between knowledge and lifestyle, there are notable gender implications of Upanishadic teachings. Yājñavalkya, for example, assumes that the main knowers of the self will be brahmin men, even claiming that through knowledge of the self one can become a brahmin (BU 4.4.23). The word “ātman” is grammatically masculine and teachings of the self are directed specifically towards a male audience and articulated in overtly androcentric metaphors (Black 2007: 135-41). Nonetheless, a number of teachings of the self suggest that true knowledge goes beyond gender distinctions. As we have seen, Uddālaka Āruṇi describes the self as an organic, universal life-force, while Yājñavalkya teaches that one who knows the self will see the self in all living beings (BU 4.4.23). It is also noteworthy that the Upaniṣads depict several women—such as Gārgī and Maitreyī—as participating in philosophical discussions and debates (Black 2007: 48-67; Lindquist 2008).

The Upaniṣads and Hindu Darśanas before Vedānta

The influence of the Upaniṣads on the so-called ‘Hindu’ darśanas is more oblique than explicit, with few direct references, yet with many of the dominant terms and concepts seemingly inherited from them. Many of the six main Hindu schools officially recognize the Upaniṣads as a source of philosophy in so far as they recognize śabda as a valid means for attaining knowledge. Śabda literally means ‘word’, but in philosophical discourse, it refers to verbal testimony or reliable authority, and is sometimes taken to refer specifically to śruti. Despite the nominal acceptance of śabda as a pramāṇa, however, the Upaniṣads are only cited occasionally in the surviving texts, and rarely as a source to validate fundamental arguments, before the emergence of the Vedānta school in the 7th century.

Notably, the Upanishadic notion of self—as a spiritual essence separate from the physical body—is generally accepted by the classical Hindu philosophical schools. The Nyāya and Mīmāṃsā darśanas, for example, which do not cite the Upaniṣads to prove its existence, nevertheless describe the self as an immaterial substance that resides in and acts through the body. In addition to conceptual similarities with certain passages from the Upaniṣads, both schools seem to consider the Upaniṣads as texts that specialize in the self. The Nyāya philosopher Vātsyāyana (c. 350-450 C.E.), for instance, characterizes the Upaniṣads as dealing with the self.

Similarly, the early texts of the Sāṃkhya and Yoga darśanas do not refer to the Upaniṣads when making their fundamental arguments but do seem to inherit much of their terminology, as well as some of their views, from them. At the beginning of Uddālaka Āruṇi’s instruction to Śvetaketu in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (6.2-5), for instance, he describes existence (sat) as consisting of three forms (rūpas): fire (red), water (white), and food (black)—a scheme that closely resembles the later Sāṃkhya doctrine of prakṛti and the three guṇas. The Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad (4.5), the oldest extant text to use the word “sāṃkhya” (5.2), seems to build on Uddālaka’s three-fold scheme when describing the unborn as red, white, and black. Also, a number of core terms in Sāṃkhya philosophy first appear in the Upaniṣads, such as ahaṃkāra (CU 7.25.1) and the tattvas (BU 4.5.12), while some passages contain groups of terms appearing together in ways that are similar to how they appear in later Sāṃkhya texts: the Kaṭha Upaniṣad (3.10-11), for example, lists a hierarchy of principles including person (puruṣa), discernment (buddhi), mind (manas), and the sense capacities (indriyas).

A number of details about the practice of yoga, which would become more systematized by the Yoga darśana, are also first found in the Upaniṣads. The Kaṭha (3.3-13; 6.7-11) and Śvetāśvatara (2.8-11) Upaniṣads both contain some of the earliest descriptions of exercises for controlling the senses, breathing techniques, and bodily postures, with the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad (for example, 2.15-17) making explicit connections between yogic practice and union with a personal god—a connection that would be of central importance in the Yoga darśana. The Maitrī Upaniṣad (6-7) has the most extensive and systematic discussion of yoga in the Upaniṣads, containing a number of parallels with the Yoga Sūtra.

In addition to employing terms and concepts from the Upaniṣads, there are occasions when classical Indian philosophers refer to the Upaniṣads directly. Vātsyāyana, of the Nyāya school, quotes passages from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka and Chāndogya Upaniṣads when discussing mokṣa, the means of attaining it, and the stages of life. Additionally, the grammarian Patañjali (c.150 B.C.E.) argues that the study of grammar is useful for a correct understanding of passages from the Upaniṣads, and thus for attaining mokṣa.

Such examples indicate that the philosophers of classical Hindu philosophy knew the Upaniṣads quite well and would dip into the texts from time to time to provide an analogy or, occasionally, to support one of their arguments. However, the early surviving texts of the Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Mīmāṃsā, Sāṃkhya, and Yoga schools do not tend to use the Upaniṣads to validate their core positions. The Vaiśeṣika Sūtra (3.2.8), for example, agrees that the self is discussed in the Upaniṣads, but then argues that the proof of the existence of the self should not be established exclusively by means of śruti, but also can be determined through inference. Additionally, none of the early schools produced a commentary on the Upaniṣads, nor did any of them aim to offer an interpretation on the Upaniṣads as a whole. As such, the Upaniṣads provided a general philosophical framework, as well as serving as a repository for terms and analogies, but none of the early schools claimed the texts for themselves.

An interesting illustration of this point is that competing schools would sometimes recognize that their rival’s positions were also to be found in the Upaniṣads. The Nyāya philosopher Jayanta Bhaṭṭa even finds the positions of the heterodox Lokāyata darśana, or Materialist school, in the Upaniṣads. In the context of criticizing the validity of śabda as a pramāṇa, Bhaṭṭa argues that if śabda were a valid means for establishing knowledge, then even the doctrines of the Lokāyatas must be true because their doctrines can be found in the Upaniṣads. Due to a lack of sources from the Lokāyata school, we do not know if they ever referred to the Upaniṣads in their own texts, but Bhaṭṭa’s argument is illustrative of a general reluctance of most of the early schools to put too much stake in śruti as a means of knowledge. His comments are also an acknowledgment that the Upaniṣads contain a variety of viewpoints.

The Upaniṣads and Vedānta

The oldest surviving systematic interpretation of the Upaniṣads is the Brahma Sūtra (200 B.C.E.—200 C.E.), attributed to Bādarāyaṇa. Although technically not a commentary (that is, it is a sūtra rather than a bhāṣya), the Brahma Sūtra is an explanation of the philosophy of the Upaniṣads, treating the texts as the source for knowledge about Brahman. Despite being considered a Vedānta text, the Brahma Sūtra (a.k.a. Vedānta Sūtra) was composed centuries before the establishment of Vedānta as a philosophical school. The Brahma Sūtra uses the Upaniṣads to refute the position of dualism, as put forth by the Sāṃkhya school. Like Śaṅkara does later, the Brahma Sūtra (1.1.3-4) states that śruti is the source of all knowledge about Brahman. Additionally, the Brahma Sūtra maintains that mokṣa is the ultimate goal as opposed to action or sacrifice.

Centuries later, the Vedānta darśana was the first philosophical school to attempt to present the Upaniṣads as holding a unified philosophical position. Vedānta means ‘end of the Vedas’ and is often used to refer specifically to the Upaniṣads. The school divides the Vedas into two sections: karmakānda, the section of spiritual exegesis (consisting of the Saṃhitās and the Brāhmaṇas), and jñānakānda, the section of knowledge (consisting of the Upaniṣads, and to a certain extent, the Āraṇyakas). According to the Vedānta school, the ritual section contains detailed instructions on how to perform the rituals, whereas the Upaniṣads contain transcendent knowledge for the sake of achieving mokṣa. There are three main branches of the Vedānta school: Advaita Vedānta, Viśiṣtādvaita Vedānta, and Dvaita Vedānta. Although these branches would put forth distinct philosophical positions, they all took śabda as the exclusive means to knowledge about its central doctrines and considered the Upaniṣads, the Brahma Sūtra, and Bhagavad Gītā as its core texts (prasthānatraya). Despite disagreeing with each other, all three of the most well-known philosophers of the Vedānta school—Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, and Madhva—wrote commentaries on the Upaniṣads, presenting them as having a single, and consistent philosophical position.

The most well-known philosopher of the Vedānta school was Śaṅkara (c. 700 C.E.), whose interpretations of the Upaniṣads made a major impact on the Indian philosophical tradition in the centuries after his lifetime and continued to dominate readings of the texts throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Śaṅkara was the main proponent of Advaita Vedānta, which put forth a position of non-dualism. According to Śaṅkara the fundamental teaching of the Upaniṣads is that ātman and brahman are one and the same.

For Śaṅkara, the Upaniṣads are not merely sources to back up his claims, but they also provide him with techniques for making his arguments. Śaṅkara takes the Upaniṣads as outlining methods for their own interpretation, following a number of literary criteria as clues for how to read the texts (Hirst 2005: 59-64). Consequently, even when he uses examples not found in the Upaniṣads, Śaṅkara can maintain that his arguments are based on scripture, for as long as he argues in the same way that the Upaniṣads do, he can claim that his arguments are based on his sources.

Despite the significance of Śaṅkara’s philosophy, it is important to note that his interpretation of the Upaniṣads was not the only one accepted by philosophers of the Vedānta school. Rāmānuja (c. 1000 C.E.), the main proponent of a form of Vedānta known as Viśiṣtādvaita, or qualified non-dualism, used the Upaniṣads to argue that ātman is not identical with brahman, but an aspect of brahman. Rāmānuja also found in the Upaniṣads a source for bhakti, as he identified the Upanishadic Brahman with God. Two centuries later, Madhva (c. 1200 C.E.) used the Upaniṣads as a source for a dualist branch of the school, known as Dvaita Vedānta. Madhva interpreted brahman as an infinite and independent God, with the self as finite and dependent. As such, ātman is dependent upon brahman, but they are not exactly the same.

It is well known that the Vedānta school became extremely influential in shaping subsequent philosophical debates, and we may conjecture that the tendency for various Vedānta philosophers to use the Upaniṣads in support of their own positions, as well as in their criticisms of rival schools, prompted other schools to engage with the Upaniṣads more closely. This is illustrated by the fact that schools such as Nyāya and Sāṃkhya, which previously seem to have relied very little on the Upaniṣads, began invoking them to counter the claims of Advaita Vedānta.

The Nyāya philosopher Bhāsarvajña (c. 850-950 CE), for example, quotes some verses from the Upaniṣads to support his position of a distinction between the ordinary and supreme sense of self when arguing with the Advaita position of non-dualism. Another Nyāya philosopher, Gaṅgeśa (c. 1300 C.E.), seems to be quoting from the Upaniṣads to back up the claim that karmic retribution is not binding for those who know the self—a position stated by Yājñavalkya (BU 4.4.23). Moreover, a number of Sāṃkhya and Yoga philosophers use the Upaniṣads in an attempt to make their schools more compatible with Vedānta. The Sāṃkhya philosopher Nāgeśa (c. 1700-1750), for example, draws from the Upaniṣads—as well as the other two source texts of the Vedānta school, the Bhagavad Gītā and Brahma Sūtra—to argue that the Vedānta and Sāṃkhya schools do not contradict each other. This trend can also be found in the Sāṃkhyasūtra (c. 1400-1500 C.E.), which argues that the identification of Brahman and ātman was a qualitative identity, but not a numerical one—seemingly defending Sāṃkhya against Śaṅkara’s criticism that the Sāṃkhya doctrine of multiple selves contradicts the Upaniṣads. Interestingly, this argument suggests that Sāṃkhya philosophers not only felt the need to show that their positions did not contradict the Upaniṣads, but also that they basically accepted the Advaita Vedānta reading of the Upaniṣads.