Religion is never merely metaphysics. For all peoples the forms and objects of worship are suffused with an aura of deep moral seriousness. The holy bears within it everywhere a sense of intrinsic obligation: it not only encourages devotion, it demands it; it not only induces intellectual assent, it enforces emotional commitment. Whether it be formulated as Brahman or as the Holy Trinity, that which is set apart as more than mundane is inevitably considered to have far-reaching implications for the direction of human conduct. Never merely metaphysics, religion is never merely ethics either. The source of its moral vitality is conceived to lie in the fidelity with which it expresses the fundamental nature of reality. The powerfully coercive “ought” is felt to grow out of a comprehensive factual “is,” and in such a way religion grounds the most specific requirements of human action in the most general contexts of human existence.

In recent anthropological discussion, the moral (and aesthetic) aspects of a given culture, the evaluative elements, have commonly been summed up in the term “ethos,” while the cognitive, existential aspects Ethos, World view of life, and the Analysis of Sacred Symbols have been designated by the term “world view of life.” A people’s ethos is the tone, character, and quality of their life, its moral and aesthetic style and mood; it is the underlying attitude toward themselves and their world that life reflects. Their world view of life is their picture of the way things in sheer actuality are, their concept of nature, of self, of society. It contains their most comprehensive ideas of order. Religious belief and ritual confront and mutually confirm one another ; the ethos is made intellectually reasonable by being shown to represent a way of life implied by the actual state of affairs which the world view of life describes, and the world view of life is made emotionally acceptable by being presented as an image of an actual state of affairs of which such a way of life is an authentic expression. This demonstration of a meaningful relation between the values a people holds and the general order of existence within which it finds itself is an essential element in all religions, however those values or that order be conceived. Whatever else religion may be, it is in part an attempt (of an implicit and directly felt rather than explicit and consciously thought-about sort) to conserve the fund of general meanings in terms of ·which each individual interprets his experience and organizes his conduct.

But meanings can only be “stored” in symbols: a cross, a crescent, or a feathered serpent. Such religious symbols, dramatized in rituals or related in myths, are felt somehow to sum up, for those for whom they are resonant, what is known about the way the world is, the quality of the emotional life it supports, and the way one ought to behave while in it. Sacred symbols thus relate an ontology and a cosmology to an aesthetics and a morality: their peculiar power comes from their presumed ability to identify fact with value at the most fundamental level, to give to what is otherwise merely actual, a comprehensive normative import. The number of such synthesizing symbols is limited in any culture, and though in theory we might think that a people could construct a wholly autonomous value system independent of any metaphysical referent, an ethics without ontology, we do not in fact seem to have found such a people. The tendency to synthesize world view of life and ethos at some level, if not logically necessary, is at least empirically coercive; if it is not philosophically justified, it is at least pragmatically universal.

It is a cluster of sacred symbols, woven into some sort of ordered whole, which makes up a religious system. For those who are committed to it, such a religious system seems to mediate genuine knowledge, knowledge of the essential conditions in terms of which life must of necessity be lived. Particularly where these symbols are criticized, historically or philosophically, as they are in most of the world’s cultures, individuals who ignore the moral aesthetic norms the symbols formulate, who follow a discordant style of life are regarded not so much as evil as stupid, insensitive, unlearned, or in the case of extreme dereliction mad.

Morality has thus the air of simple realism, of practical wisdom ; religion supports proper conduct by picturing a world in which such conduct is only common sense.

The sort of counterpoint between style of life and fundamental reality which the sacred symbols formulate varies from culture to culture. For the Navaho, an ethic prizing calm deliberateness, untiring persistence, and dignified caution complements an image of nature as tremendously powerful, mechanically regular, and highly dangerous.

For the French, a logical legalism is a response to the notion that reality is rationally structured, that first principles are clear, precise, and unalterable and so need only be discerned, memorized, and deductively applied to concrete cases.

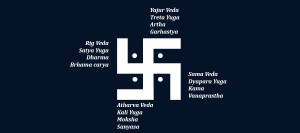

For the some people, a transcendental moral determinism in which one’s social and spiritual status in a future incarnation is an automatic outcome of the nature of one’s action in the present, is completed by a ritualistic duty-ethic bound to caste. In itself, either side, the normative or the metaphysical, is arbitrary, but taken together they form a gestalt with a peculiar kind of inevitability.

What all sacred symbols assert is that the good for man is to live realistically, where they differ is in the vision of reality they construct.

However, it is not only positive values that sacred symbols dramatize, but negative ones as well. They point not only toward the existence of good but also of evil, and toward the conflict between them. The so called problem of evil is a matter of formulating in world-view terms

the actual nature of the destructive forces within the self and outside of it, of interpreting murder, crop failure, sickness, earthquakes, poverty, and oppression in such a way that it is possible to come to some sort of terms with them.

The force of a religion in supporting social values rests, then, on the ability of its symbols to formulate a world in which those values, as well as the forces opposing their realization, are fundamental ingredients. It represents the power of the human imagination to construct an image of reality.

Max Weber “events are not just there and happen, but they have a meaning and happen because of that meaning.”

The need for such a metaphysical grounding for values seems to vary quite widely in intensity from culture to culture and from individual to individual, but the tendency to desire some sort of factual basis for one’s commitments seems practically universal, mere conventionalism satisfies few people in any culture. However its role may differ at various times for various individuals and in various cultures, religion by fusing ethos and world view of life of life, gives to a set of social values what they perhaps most need to be coercive an appearance of objectivity.

In sacred rituals and myths values are portrayed not as subjective human preferences but as the imposed conditions for life implicit in a world with a particular structure.

The sort of complexes symbol regarded by a people as sacred varies very widely. Elaborate initiation rites, as among the Australians ; complex philosophical tales, as among the Maori ; dramatic shamanistic exhibitions, as among the Eskimo; cruel human sacrifice rites, as among the Aztecs; obsessive curing ceremonies, as among the Navaho; large communal feasts, as among various Polynesian groups all these patterns and many more seem to one people or another to sum up most powerfully what it knows about living.

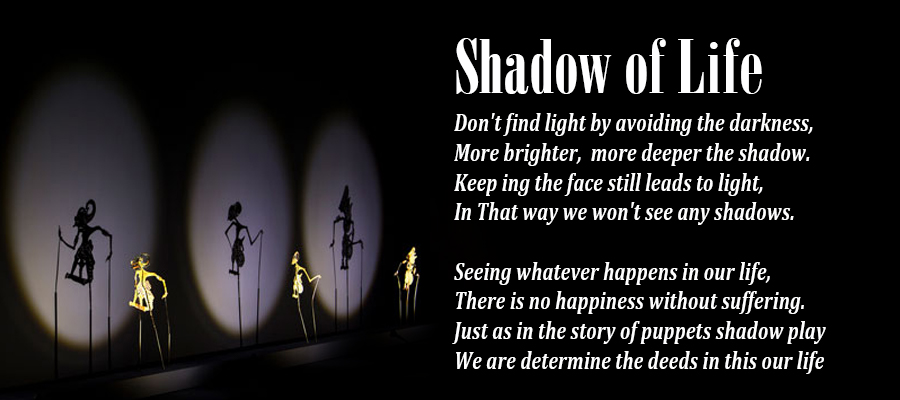

One of the most deeply rooted and highly developed of their art forms which is at the same time a religious rite is the shadow puppet play or called “Wayang”.

The stories are mostly episodes taken from the epic Mahabarata, somewhat adapted and placed in setting Ethos, World view of life and the Analysis of Sacred Symbols (Stories from the Ramayana).

The two most important groups of these nobles are the Pendawas and the Korawas. The Pendawas are the famous five hero brothers-Yudistira, Bima, Arjuna, and the identical twins, Nakula and Sadewa who are usually accompanied as a general advisor and protector by Krisna, an incarnation of Visnu. The Korawas, of whom there are a hundred, are cousins of the Pendawas.

They have usurped the kingdom of Astina from them, and it is the struggle over this disputed country which provides the major theme of the wayang, a struggle which culminates in the great Bratajuda war of kinsmen, as related in the Bhagavad Gita, in which the Korawas are defeated by the Pendawas.

The world view of life the Wayang expresses, despite the surface similarities in the two feudal codes. It is not the external world of principalities and powers which provides the main setting for human action, but the internal one of sentiments and desires. Reality is looked for not outside the self, but within it.

For the people of subjective experience taken in all its phenomenological immediacy, presents a microcosm of the universe generally in the depths of the fluid interior world of thought and emotion they see reflected ultimate reality itself.

This inward looking sort of world view of life is best expressed in a concept have also borrowed from those ethos and also peculiarly reinterpreted ad “Rasa” or feeling.

Feeling it is one of the five senses; seeing, hearing, talking, smelling, and feeling, and it includes within itself three aspects of feeling that our view of the five senses separates: taste on the tongue, touch on the body, and emotional feeling within the heart, like sadness and happiness.

Feeling said one of my most articulate informants is the same as life, whatever lives has feeling and whatever has feeling lives. To translate such a sentence one could only render it twice: whatever lives feels and whatever feels lives, or whatever lives has meaning and whatever has meaning lives, which this quiescence makes possible is gnosis the direct comprehension of the ultimate feeling.

God is found by means of spiritual discipline in the depths of the self as pure feeling. And ethics and aesthetics are correspondingly, affect-centered without being hedonistic: emotional equanimity, a certain flatness of affect, a strange inner stillness, is the prized psychological state, the mark of a truly noble character.

One must attempt to get beyond the emotions of everyday life to the genuine feeling, meaning which lies within us all. Happiness and unhappiness are, after all just the same. You shed tears when you laugh and also when you cry. And besides, they imply one another: happy now, unhappy later; unhappy now, happy later.

The wise man strives not for happiness, but for a tranquil detachment which frees him from his endless oscillation between gratification and frustration. Similarly which comprises almost the whole of this morality, focuses around the injunction not to disturb the equilibrium of another by sudden gestures, loud speech, or startling, erratic actions of any sort, mainly because so doing will cause the other in turn to act erratically and so upset one’s own balance.

As proverb says “If you start off north, go north, don’t turn east, west, or south.” Both religion and ethics, both mysticism and politesse, thus point to the same end: a detached tranquility which is proof against disturbance from either within or without.

This tranquility is not to be gained by a retreat from the world and from society, but must be achieved while in it. It is a this worldly, even practical, mysticism, as expressed in the following composite quotation from someone who are members of a mystical society :

He said that the society was concerned with teaching you not to pay too much attention to worldly things, not to care too much about the things of everyday life. He said this is very difficult to do. His wife, he said, was not by taking feeling to mean both feeling and meaning, the more speculatively inclined among have been able to develop a highly sophisticated phenomenological analysis of subjective experience to which everything else can be tied. Because fundamentally feeling and meaning are one, and therefore the ultimate religious experience taken subjectively is also the ultimate religious truth taken objectively, an empirical analysis of inward perception yields at the same time a metaphysical analysis of outward reality. This being granted and the actual discriminations, categorizations, and connections made are often both subtle and detailed-then the characteristic way in which human action comes to be considered from either a moral or an aesthetic point of view, is in terms of the emotional life of the individual who experiences it.

This is true whether this action is seen from within as one’s own behavior or from without as that of someone else: the more refined one’s feelings, then the more profound one’s understanding, the more elevated one’s moral character, and the more beautiful one’s external aspect, in clothes, movements, speech, and so on.

The spiritually enlightened man guards well his psychological equilibrium and makes a constant effort to maintain its placid stability. His inner life must be, in a simile repeatedly employed, like a still pool of clear water to the bottom of which one can easily see. The individual’s proximate aim is, thus, emotional quiescence, for passion is crude feeling, fit for children, animals, madmen, primitives, and foreigners. But his ultimate aim, yet able to do it much, and she agreed with him.

It takes much long study. For example, you have to get so that if someone comes to buy cloth you don’t care if he buys it or not . . . and you don’t get your emotions really involved in the problems of commerce, but just think of God and avoids any strong attachments to everyday life.

This fusion between a mystical phenomenological world view of life and an etiquette centered ethos is expressed in the Wayang in various ways. First, it appears most directly in terms of an explicit iconography.

The five Pendawas are commonly interpreted as standing for the five senses which the individual must unite into one undivided psychological force in order to achieve gnosis. Meditation demands a “cooperation” among the senses as close as that among the hero brothers, who act as one in all they do. Or the shadows of the puppets are identified with the outward behavior of man, the puppets themselves with his ·inward self, so that in him as in them the visible pattern of conduct is a direct outcome of an underlying psychological reality. The very design of the puppets has explicit symbolic significance: in Bima’s red, white, and black sarong, the red is usually taken to indicate courage, the white purity, the black fixity of will. The various tunes played on the accompanying game/an orchestra each symbolize a certain emotion ; similarly with the poems the dalang sings at various points in the play, and so on. Second, the fusion often appears as parable, as in the story of Bima’s quest for the “clear water.” After slaying many monsters in his wanderings in search of this water which he has been told will make him invulnerable, he meets a god as big as his little finger who is an exact replica of himself. Entering through the mouth of this mirror-image midget, he sees inside the god’s body the whole world, complete in every detail, and upon emerging he is told by the god that there is no “clear water” as such, that the source of his own strength is within himself, after which he goes off to meditate. And third, the moral content of the play is sometimes interpreted analogically: the dalang’s absolute control over the puppets is said to parallel God’s over men ; or the alternation of polite speeches and violent wars is said to parallel modern international relationships, where so long as diplomats continue talking, peace prevails, but when talks break down, war follows.

But neither icons, parables, nor moral analogies are the main means by which the Javanese synthesis is expressed in the Wayang; for the play as a whole is commonly perceived to be but a dramatization of individual subjective experience in terms at once moral and factual :

He an elementary school teacher said that the main purpose of the Wayang was to draw a picture of inner thought and feeling, to give an external form to internal feeling. He said that more specifically it pictured the eternal conflict in the individual between what he wanted to do and what he felt he ought to do. Suppose you want to steal something. Well, at the same time something inside you tells you not to do it, restrains you, controls you. That which wants to do it is called the will ; that which restrains is called the ego. All such tendencies threaten every day to ruin the individual, to destroy his thought and upset his behavior. These tendencies are called goda, which means something which plagues or teases someone or something. For example, you go to a coffee shop where people are eating. They invite you to join them, and so you have a struggle within-should I eat with them … no, I’ve already eaten and I will be over full . . . but the food looks good . . . etc.

Well, in the Wayang the various plagues, wishes, etc. the godas are represented by the hundred Korawas, and the ability to control oneself is represented by their cousins, the five Pendawas and by Krisna. The stories are ostensibly about a struggle over land. The reason for this is so the stories will seem real to the onlookers, so the abstract elements in the feeling can be represented in concrete external elements which will attract the audience and seem real to them and still communicate its inner message. For example, the Wayang is full of war and this war, which occurs and reoccurs, is really supposed to represent the inner war which goes on continually in every person’s subjective life between his base and his refined impulses.

This formulation is more self-conscious than most the average man “enjoys” the Wayang without explicitly interpreting its meaning, so the sacred symbols of the Wayang, the music, characters, the action itself give form to the ordinary experience.

For example, each of the three older Pendawas are commonly held to display a different sort of emotional moral dilemma, centering around one or another of the central Javanese virtues. Yudistira, the eldest, is too compassionate. He is unable to rule his country effectively because when someone asks him for his land, his wealth, his food, he simply gives it out of pity, leaving himself powerless, poor, or starving. His enemies continually take advantage of his mercifulness to deceive him and to escape his justice.

Bima, on the other hand, is single-minded, steadfast. Once he forms an intention, he follows it out straight to its conclusion; he doesn’t look aside, doesn’t turn off or idle along the way he goes north. As a result, he is often rash, and blunders into difficulties he could as well have avoided. Arjuna, the third brother, is perfectly just. His goodness comes from the fact that he opposes evil, that he shelters people from injustice, that he is coolly courageous in fighting for the right. But he lacks a sense of mercy, of sympathy for wrong doers. He applies a divine moral code to human activity, and so he is often cold, cruel, or brutal in the name of justice.

The resolution of these three dilemmas of virtue is the same: mystical insight. With a genuine comprehension of the realities of the human situation, a true perception of the ultimate rasa, comes the ability to combine Yudistira’s compasion, Bima’s will to action, and Arjuna’s sense of justice into a truly moral outlook, an outlook which brings an emotional detachment and an inner peace in the midst of the world of flux, yet permits and demands a struggle for order and justice within such a world. And it is such a unification that the unshakable solidarity among the Pendawas in the play, continually rescuing one another from the defects of their virtues, clearly demonstrates.

The view of man as a symbolizing, conceptualizing, meaning seeking which has become increasingly popular both in the social sciences and in philosophy over the past several years, opens up a whole new approach not only to the analysis of religion, but to understanding of the relations between religion and values. The drive to make sense out of experience, to give it form and order, is evidently as real and as pressing as the more familiar biological needs. And, this being so, it seems necessary to continue to interpret symbolic activities religion, art, ideology as thinly disguised expressions of something other than what they seem to be attempts to prov ide orientation for an organism which cannot live in a world it is unable to understand.

If symbols, to adapt a phrase of Kenneth Burke’s, are strategies for encompassing situations, then we need to give more attention to how people define situations and how they go about coming to terms with them. Such a stress does not imply a removal of beliefs and values from their psychobiological and social contexts into a realm of “pure meaning,” but it does imply a greater emphasis on the analysis of such beliefs and values in terms of concepts explicitly designed to deal with symbolic material.

Anthropologists are beginning to develop an approach to the study of values which can clarify rather than obscure the essential processes involved in the normative regulation of behavior. One almost certain result of such an empirically oriented, theoretically sophisticated, symbol-stressing approach to the study of values is the decline of analyses which attempt to describe moral, aesthetic, and other normative activities in terms of theories based not on the observation of such activities but on logical considerations alone. Like bees who fty despite theories of aeronautics which deny them the right to do so, probably the overwhelming majority of mankind are continually drawing normative conclusions from factual premises (and factual conclusions from normative premises, for the relation between ethos and world view of life is circular) despite refined, and in their own terms impeccable, reflections by professional philosophers on the “naturalistic fallacy.” An approach to a theory of value which looks toward the behavior of actual people in actual societies living in terms of actual cultures for both its stimulus and its validation will turn us away from abstract and rather scholastic arguments in which a limited number of classical positions are stated again and again with little that is new to recommend them, to a process of ever-increasing insight into both what values are and how they work .

Once this enterprise in the scientific analysis of values is well launched, the philosophical discussions of ethics are likely to take on more point. The process is not that of replacing moral philosophy by descriptive ethics, but of providing moral philosophy with an empirical base and a conceptual framework Which is somewhat advanced over that available to Aristotle, Spinoza, or G. E. Moore. The role of such a special science as anthropology in the analysis of values is not to replace philosophical investigation, but to make it relevant.